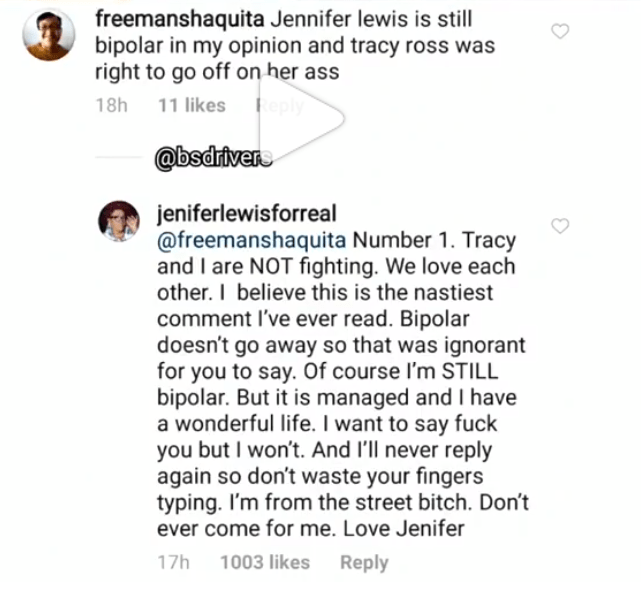

BPD, which stands for Borderline Personality Disorder, has significant areas of overlap with bipolar disorder. Both disorders implicate a breakdown in the emotion regulation areas of the brain. But what are the differences? Cross-sectionally, they’re sometimes quite difficult to tell apart. More differences emerge when looking longitudinally across time.

- Bipolar is episodic and predictable in the short term: episodes of mania and depression (and mixed episodes) come and go in a fairly predictable fashion. Some people have depression first and then fly into mania, while others start out with a manic episode and then crash into the depression. It’s roughly 50-50 between these patterns, but within individuals the pattern stays consistent. Which is to say, if you’re a mania first bipolar, you’ll most likely always be mania first.

- BPD breakdowns tend to be triggered by some situation the person has found themselves in. Their responses may be over-exaggerated but there is some kind of trigger. Bipolar episodes can also be triggered sometimes, but classically, bipolar episodes can occur with no trigger at all. They’re related to a sort of internal thermostat which is broken. Thus, time of year — and changes in sunlight, which affects this internal thermostat — can be triggers for bipolar disorder, and less likely for BPD.

- Psychosis is much more pronounced in bipolar disorder than in BPD. The classic euphoric mania with grandiose delusions come to mind; in bipolar disorder, psychosis is limited to mood episodes and is almost always mood-congruent. (Meaning, someone with classic euphoric mania might have grandiose delusions that they are a very important person or have special powers or abilities; meanwhile, someone in a mixed episode might hear muffled voices that make them feel very paranoid about who might be watching, and they see bugs crawling all over the walls. Okay, the mixed episode examples are psychotic features I have experienced myself.) BPD people may experience transient, stress-related psychosis, but they don’t hold onto it as strongly as bipolar people.

- Sleep and changes in sleep are arguably the most important symptoms for bipolar people. Not sleeping enough feeds into mania, while sleeping too much feeds into depression. The relationship between BPD and sleep is less clear. Lack of sleep may worsen emotion regulation challenges. People with BPD who don’t get enough sleep are likely to be irritable during the day.